🧠 Can carbs really prevent concussions? Tua Tagovailoa thinks so—and the media ran with it.

Tua Tagovailoa didn’t get a concussion — so which miracle worked this time?

Last week, Miami Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa took a blow to the head. His helmet hit the ground. He got up, finished the game, and later told reporters his secret to avoiding concussions:

More carbs and fluids.

“You’d probably think it’d make you heavier or slow you down in a way, for sure. But I guess for me, from what I’ve come to know or come to understand from what the doctors were talking about, is your brain kind of sits in fluids, and if I’m eating eggs, bacon and sausage and there’s not much carbs, like if there’s no bread or whatnot, you kind of drink water and it’ll just flush out of you, so you can’t stay hydrated that way. But the carbs kind of help soak that in and stay there.”

In other words: Eat bread, protect brain…

NBC Sports dutifully relayed the quote and added the softest possible disclaimer — “It’s unclear whether it’s enough to keep the brain from becoming injured.”

Bleacher report didn’t question the claim, but expressed optimism: “…hopefully the steps he is taking to protect himself as much as possible keep working.”

Is this where we are really at now? Taking wild claims about concussion prevention and hoping for the best? And when a player doesn’t get a concussion, using that as evidence it works?

Let’s dive in a bit more.

🧩 Not Tua’s first concussion prevention plan

To understand why this matters, you have to rewind to 2022.

In Week 3 against Buffalo, Tua took a hard hit, stumbled, and grabbed his helmet — a classic red flag for neurological impairment. He was examined, declared fine, and sent back into the game. The Dolphins said it was a “back injury.”

Four days later, against Cincinnati, he was knocked unconscious. His hands stiffened in the fencing posture, and the NFL faced its biggest concussion scandal in years.

The league eventually admitted the first evaluation was botched and rewrote its return-to-play protocol.

That trauma shaped Tua’s entire 2023 season. In June of 2023, here reported that he trained in Brazilian jiu-jitsu to “learn how to fall better,” worked on neck strengthening to prevent concussions.

That season, he was not reported to have any concussions. Is that evidence the Jiu Jitsu training worked? To some, the answer was yes. A Fox news article quoted Dolphin’s general manager Chris Grier stating “Spending the time learning to fall, with the jiujitsu and stuff, it paid off for him.” They also reported that Dolphins’ head coach Mike McDaniel was “comfortable” with the jiu jitsu prevention plan and that other prevention plans “weren’t as good as that one.”

But, in September 2024, he got another concussion. Did he stop doing jiu jitsu? Or did the jiu jitsu just not work? Or could we just explain it away as “well, jiu jitsu reduces his concussion risk by a lot, but it can’t prevent all concussions?”

Attribution Bias

Now, in 2025, he’s promoting carb loading to stay healthy. And, he didn’t get a concussion after a big hit. We’re five weeks in and no concussions.

So, the carbs must be working… right? Or is it the jiu-jitsu? Or both? Or is it simply that even the most concussion-prone players, like Tua, don’t get a concussion on every hit in every game?

Tua claiming that a lack of concussion is evidence that his high carb diet is working is a textbook case of attribution bias — our instinct to connect a good outcome to whatever recent change we made.

I wrote about this kind of thinking in more depth in my piece on causes of sudden cardiac arrest in athletes, which explores how we reach for simple explanations in the face of tragedy — and how our brains reward us for doing so.

And for a lighter example of how bias colors our sense of cause and effect, see my “Taylor Swift effect” piece, where I unpack the same mental shortcuts that lead sports fans and Swifties alike to find meaning — and causality — where none exists.

When something stops going wrong, we want to believe it’s because we finally found the fix. But sometimes, the pattern exists only in the story we tell ourselves.

🍞 The Science of Bread-Based Brain Loading

Tua isn’t entirely wrong that carbohydrates fuel the brain — but the claims that it can help prevent concussions are, at best, untested, at worst, dangerously non-sensical.

When we talk about “carb loading” for endurance sports, we refer to filling up your muscles and liver with the storage form of carbohydrates, known as glyogen. Glycogen does attract water molecules, so yes, it is putting more water into the muscles. This doesn’t mean the muscles were dehydrated without glycogen, rather it just means they have even more water in them when glycogen stores are high. Some athletes report that their muscles feel a bit stiffer or they even feel slower because of this.

Just how much glyogen is stored in your muscles? The units we typically use are something called micromoles (abbreviated µmol) per gram of muscle tissue. (There’s lots of nuance to these numbers, depending if we are measuring by wet or dry weight, etc. so we will make broad statements here).

For skeletal muscle, we typically have around 350-400 µmol glycogen per gram of tissue, writen as 350-400µmol/g. If we carb load, we raise that to 500 to 700+µmol/g. Liver glycogen is also in that general range.

But, the brain? A measly 3-8µmol/g. That’s about 50–100 times lower than muscle or liver. So, extrapolating the idea of carb loading from muscle to brain is… ambitious.

Human studies using magnetic resonance spectroscopy show that brain glycogen turns over slowly, taking 3–5 days to fully renew. It doesn’t spike after a pasta dinner. Instead, it rises after the brain has been metabolically stressed and then recovers — for example, following prolonged hypoglycemia or other intense energy demands. In those cases, the brain actually “supercompensates,” restoring glycogen to above baseline over several days.

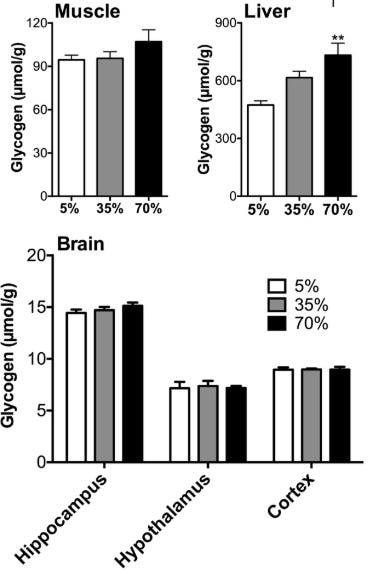

Animal studies tell a similar story. Changing diet alone had little effect on brain glycogen compared with the large changes seen in muscle and liver. Check out the figures below, showing how different diet types (5% carbs, 35% carbs, 70% carbs) changed glycogen content in rats across different tissues. Major effects in the muscles and liver. In the brain? Not much of an effect.

The real driver was exhaustive exercise. When rats performed strenuous, near-exhaustive activity and ate a high-carbohydrate diet, they increased glycogen in specific regions like the hippocampus and hypothalamus by about 10–30%. In other words, the best way to increase glycogen in your brain isn’t another bagel — it’s probably running yourself to the brink of collapse.

The brain seems to stock up only after it’s been pushed to the edge, not just fed more fuel. That’s because brain glycogen isn’t a performance enhancer or a cushion — it’s a last-resort reserve, meant to help neurons survive when energy runs out.

🍞But, does this even matter?

It’s pretty clear that the brain isn’t anywhere near as responsive to carb loading as muscles or the liver. Even if it was, it would then take an additional leap of faith to conclude that carb loading appreciably increased brain hydration. Then, it would take yet another jump to conclude that the extra hydration prevented concussions… especially if that hydration came from Russell Wilson’s concussion water.

In short, you can’t “carb-load your brain” into concussion resistance. No diet can change the fact that your brain tissue is subject to high accelerations and decelerations duirng a head impact, which cause tissue deformation and ultimately, cellular-level injury.

The only way to prevent that is to stop the movement — which is why no amount of sourdough will outsmart angular momentum.

🗞️ Journalism’s Soft Concussion

The real head injury here is to critical thinking.

When athletes credit folk physiology — and reporters shrug with “it’s unclear” — it turns pseudoscience into plausible science. It’s not unclear. It’s nonsense.

By avoiding confrontation, journalists become amplifiers of belief instead of filters for accuracy and critical thinking. And the public learns, once again, that belief feels just as good as evidence.

And we become just one step away from seeing this become a reality:

🧠 The Real Lesson

Athletes like Tua aren’t villains — they’re human. After years of concussions, they crave control. Belief in carbs, hydration, or jiu-jitsu gives them something to hold onto. But, they only find out it doesn’t work when things actually go wrong.

But it’s the job of reporters, doctors, and fans to remember that comfort doesn’t equal causality.

So when a quarterback survives a head hit and says he owes it to extra pasta, the right question isn’t “Will this start a new trend?”

It’s “Are we really pretending you can out-hydrate Newton’s laws?”

For deeper dives into how belief, bias, and evidence collide across science and medicine, visit my main publication: Beyond the Abstract.

If we were designing the next generation of Brain Bread™, what would its slogan be? (“Now fortified with physics!” comes to mind.) But seriously — why do you think stories like this catch on so easily?

This was really interesting. I just shared it with my subscribers (with proper credit given to you, of course): https://open.substack.com/pub/mooreamaguire/p/fact-check-carbs-protect-brains